We are traveling in Cuba, Dan and I, along with our daughter Margot and her friend Erika. The day we arrived, I sprained my ankle.

Here’s how it happened. Dan had put the bar of soap in the shower stall, but I needed the soap at the sink. So I went to get it. Fortunately, I was barefoot, so there was no problem stepping into the shower stall to get the soap, even though (for some reason) the floor was wet. Unfortunately, I was barefoot, so, as I stepped out of the shower stall and down the small step to the tile floor of the bathroom, my left foot slipped on the wet tile, and I fell, landing with my right foot at an angle that no foot should ever land at.

Yes, it hurt.

Yes, it hurt really bad, but I knew it wasn’t broken. I know what the pain from a broken bone feels like, and this was (as I said) really bad–but it wasn’t that.

In the morning, it was a bit better, but I still couldn’t do certain key activities like, for example, going up and down stairs. Or anything involving placing my right foot behind the centerline of my body. So I stayed in the hotel with my foot up and with ice on it while everyone else got their first taste of Havana. At lunchtime, I hobbled along with the group because I was determined to miss as little as possible.

The next day was a day tour of Vinales. We spent most of the morning in the car, so no problem there, and the foot didn’t really hurt much any more.

The next day, my right foot was almost entirely blue and a bit swollen, but it didn’t hurt much, so I did the walking tour of Havana and other activities of the day without a problem.

Then it was time to move on to Cienfuegos. Beautiful Cienfuegos, the pearl of the south. I wore my flipflops for the car ride, and Dan couldn’t help but notice that my foot was swollen, and the swelling seemed to have moved up to the ankle as well. He remembered that several years ago his mother had broken her ankle and had had to take blood thinner to ensure that a blood clot did not go to her heart. Or her brain. He began to worry about blood clots and insisted that when we reached Cienfuegos, we must see a doctor.

My sweet, caring husband!

After we got settled into the casa where we were staying, we went to a clinic. This turned out to be the doctor’s house (I think), with a sign in front indicating that the doctor was available 24/7. We went in. There was no line, and the doctor was available to see me right away.But first, there was the matter of the insurance. All tourists entering Cuba are required to have medical insurance that is good in the country. The U.S. airlines automatically provide this insurance for their passengers. Did I have my boarding pass?

I did.

The doctor made a copy of it, and of my passport information, and informed me that everything was all paid for. She was very nice and seemed quite competent, pressing in various places–Does it hurt here? Here? Here?

Well, really, even though my foot was a multicolor sight to see, by this time it hardly hurt at all. “What do you think is the matter?” I asked.

There ensued a five-minute-long conversation in Spanish between the doctor and our guide, the delightful Jorge. “What is she saying?” I finally asked.

“You need to get an x-ray,” the guide said.

“Why?” I asked.

There ensued another very long conversation in Spanish.

“What’s she saying?”

“It might be broken.”

“It’s not broken!” I said, but Dan signaled me to back down. He was worried about blood clots and wanted the diagnosis to run its natural course. X-rays can show things other than bones.

I sighed. “Okay. Let’s get an x-ray.”

There was no x-ray facility at the doctor’s office, so they put me into a conveniently available ambulance, along with Dan and Jorge and my own personal nurse, and off we went.

The hospital facility had definitely seen better days, but it was fairly clean. A patient in line ahead of me at the radiology laboratory lay on his stretcher smoking a cigarette–something you’d never see in the U.S. “He’s here for an x-ray,” Dan quipped, “because he has lung cancer.” A bad joke, yes, but understandable, given the somewhat surreal circumstance.

Well, they x-rayed my foot left, right, and center; developed the film on the spot; and gave it, still dripping wet, to the nurse to take to be read.

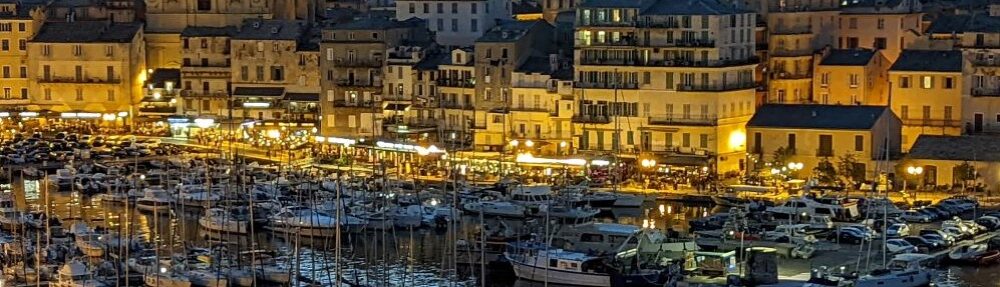

The ambulance then took us downtown, where Dan, Jorge, and I had a great walking tour of the town. My multicolored foot did not hurt. After walking a few miles up and down Cienfuegos’s beautiful streets, we took a taxi to a faux-Moorish castle by the sea for a drink and watched the sunset.

Then we walked back to the clinic. It wasn’t that far–maybe only eight blocks or so.

Behold, I did not have a broken bone! I’d been saying this from the beginning, but now I had some very graphic x-rays to prove it. And what I did now have was an anti-inflammatory cream to apply three times a day and some interesting-looking pills. No charge. Thank you, United Airlines!

“What about blood clots?” I asked.

The doctor said this was not an issue, since my foot was not in a cast, and I was very active.

“What are these for?” I asked, indicating the pills.

There ensued a lengthy conversation in Spanish between the doctor and the guide. After several minutes, I asked, “What’s she saying?”

The guide laughed and said they were discussing which they liked better: Cienfuegos or Trinidad. The doctor preferred Cienfuegos. Not so the guide.

“But what are the pills for?” I persisted.

“They will help with the swelling. And the pain,” said the doctor.

I decided not to mention that there was no longer any pain. Instead, I asked, “Can you recommend a good restaurant here in Cienfuegos?”

Her face lit up in a smile. “Oh yes!” (It turned out she could speak fairly good English, even though she was shy about it.) “There is a good one that is very expensive, and then there is one that is medium price, and it is my favorite restaurant.”

“Yes, *that* one,” Dan and I chorused.

And when it was all over, the ambulance took us back to our casa.

Not to keep you in suspense, the restaurant is El Prado. Do not confuse it with the cafe of the same name next door. We ate great food on the rooftop terrace to a live band of marvelous Afro-Cuban-jazz music. We drank two bottles of excellent South American chardonnay and entertained the marriage proposal of our waiter to either or both of our lovely young women traveling companions. An April wedding was considered. We do not know the young man’s name, but he was willing enough to call me “Mama.”

This may all seem like great lengths to go to, just to find this one marvelous restaurant, but remember, we also got to know a gracious Cuban doctor and nurse, and we experienced a Cuban hospital, and we rode in our own personal ambulance several times.

And we no longer have to worry about blood clots from my multicolored foot.