Before continuing with our next lesson in Japanese meals, I should take a moment to explain our travel. For we left Tokyo the next morning and traveled by the famous Japanese bullet train to Kurobe. Here, we were met by a car and driver sent by our hotel and whisked up into the mountains, a half-hour 20-kilometer scenic drive, to Unazuki Onsen. The Japanese word onsen means a hot spring, and indeed, steaming hot water flowed through the town.

The first thing we did was to check into our hotel, the Ryokan Enraku. A ryokan is the Japanese version of an inn, perhaps, or a B&B. This was our first of seven nights in a row in three different ryokans. They are traditional hostelries in an austere and timeless Japanese style–tatami mats on the floor, where shoes are not allowed. Slippers and robes to change into for comfort, and which are acceptable wear throughout the building. Not much furniture–just two chairs with no legs to sit on, and a low table to sit at while using such low chairs. Later, a comfortable futon on the floor for sleeping. A very personal welcome, with refreshments after your journey. Here we are, relaxing in our new digs.

Unlike the other ryokans we stayed in, this one had a balcony, and the balcony had a view of the mountain and a rushing river below. And . . . the balcony had Western-style furniture!

We had half-board at this ryokan, but before dinner we wanted to enjoy an actual Japanese onsen bath. The ryokan had, um, several of them (depending on how you count, somewhere between four and six). Occupying the first, second, and third floors, the baths are segregated by sex. There is an indoor bath for each sex on the second floor, and baths open to the outdoors on the first and third floors. Tonight, men are on the first floor and women on the third. In the morning, it will be reversed. It being early afternoon, we each have our respective baths to ourselves. We try to follow proper bath protocol but are grateful there’s no one watching in case we get something wrong. Let’s see: Undress and leave belongings in a locker. Shower before entering the bath, sitting on the little stool. Dump a bucket of water over your head to wash any dust or dirt off your hair. Rinse. Now, enter the bath. You may keep the small towel on top of your head, but leave the large towel behind. Wow, it’s HOT! But after a few seconds, amazingly good. Soak for as long as you want or can, then shower again. Use the large towel to dry off; then dress, and ooze back to your room.

Here’s a picture of an open-air onsen, possibly one of the first-floor onsens in our hotel. (It’s not mine; I didn’t take my camera there.)

Thoroughly clean and relaxed, we set out to see the town. The town wasn’t very big, so this didn’t take long. Here’s the friendly map posted at the small local train station.

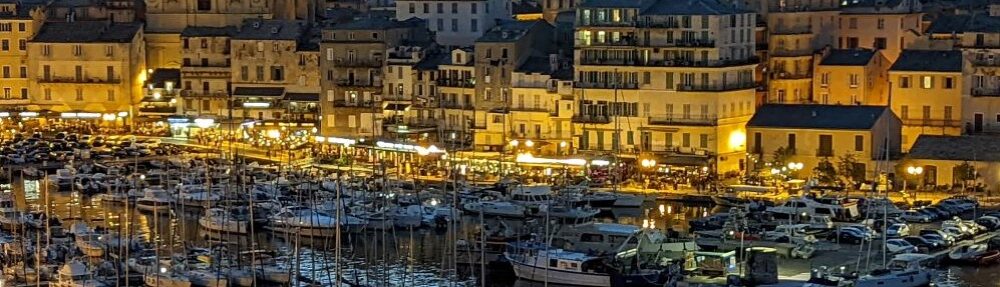

The town was nestled in the mountains, and pretty.

A gushing, naturally hot fountain in the main square lifted steam into the cool air.

Fed by the natural hot springs, foot baths were everywhere! The first one, by a restaurant, took us by surprise, but the English in the sign is self explanatory.

Some of them were beautifully designed and well integrated with modern buildings.

But now it’s time for dinner, and even in a small town in the Japanese countryside, we find an elegance to match that in Tokyo, but without the big-city pretentiousness. Here is our menu:

This is not very helpful, and, like the previous night, for the most part, the appearance of the food does not give enough of a clue as to what it actually is. It is, however, very pretty, and beautifully presented.

At last we come to a course we can understand! And it’s as delicious as it looks!

The main problem with this dinner, like the previous night, is that we get very full very quickly, and there seems no polite way *not* to eat what’s in front of us. I regret, days afterwards, having to leave half of those crab legs.

The futon on the floor is very cozy and comfortable, but in the morning we are still full.

And it’s time for the Japanese breakfast! Here’s what’s waiting for us in the morning.

And this is the way it looks when additional food is brought in.

Folks, it’s at about this point that we realize we are not going to make it through the next two days of ryokan half-board we have signed up for in our next location. But what can we do!