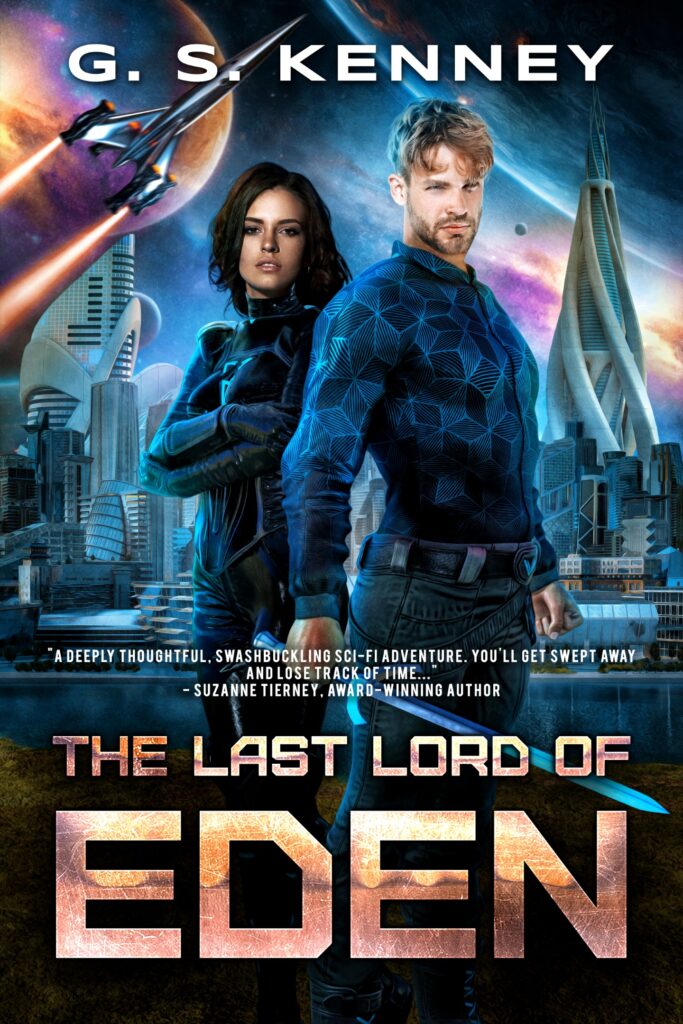

And honestly, I still don’t really want to be taking on this job of publishing. I want to keep writing new books, but I do also want to get this book into your hands and those of people everywhere who might enjoy a good science-fiction action adventure story.

It’s about perseverance and keeping promises. A city boy named Cort on the planet Aran whose best friend is abducted and sold to the aliens from Earth will stop at nothing to find and free her. When his first rescue attempt fails, he embarks on a journey to gain the skills and the help he needs to try again and succeed.

It’s about never giving up hope. Emprisoned on the aliens’ base, Cort’s friend Dilia continues to believe he will rescue her if he can. But maybe he can’t. Dilia girds herself to make the most of her time there. She learns much from the Earthers about the medicinal plants of Aran, while ever on the look-out for a way to escape.

Most of all, it’s about understanding that we are a part of a planetary ecosystem–a community larger than our neighborhoods and cities and even our nations. In Aran’s primeval forests, Cort begins having nightmares–the deep dreams of the trees that the aliens are destroying, upsetting the balance of life on the planet. And he will do what he must to protect them.

Between where they stood and the village, the forest opened up, and on a slight rise stood a man. He was of middle age, his black hair salted with grey. His vest was beaded in light and dark blue, and blue beads adorned the fringes of his dark pants. When he turned toward them, a blue crystal at his temple flashed in the sunlight. A seer!

The man stood straight and tall, his hands loosely holding a staff that extended from the ground to well above his head. Alternately rough and smooth, the staff had a slight bend as if it reached for something, and green leaves adorned a cluster of sprigs at its top. The wood of the staff gleamed in a rainbow of colors. It was the largest piece of worked khena wood Cort had ever seen.

Neder glanced at Cort, then nodded slightly as if acknowledging something someone had said to him. “It’s Tirei,” he said. “He’s the headman of my village, and a seer. He’s the one you’ll need to talk with about becoming a hunter.”

Neder set off down the hill. Cort followed him, his heart lifting, now that the end of his mission was finally in sight.

When they reached the older man, Neder introduced Cort. Tirei greeted him politely, and Cort managed a polite response, but he could barely tear his gaze from Tirei’s staff, which seemed to glow with a special light. Seen this close, it was even more remarkable than from a distance, dancing with sparks of an inner fire. His hand twitched with the desire to reach toward it.

“It is living wood,” Tirei said, following Cort’s gaze. “Would you like to touch it?”

‘Living wood’ was a good name for it. Colors and patterns swam like fish in its translucent grain. Cort didn’t trust himself to speak. He swallowed hard and nodded.

Tirei spread out his hands on the staff to open a large space between them. “Go ahead,” he said, with the kind of encouraging nod he might give to a small child trying something for the first time.

Cort stretched out his hand and took hold of the staff, then gasped in astonishment. The wood seemed alive in more ways than one. It was as if the staff had actively taken hold of his own hand. It was warm, and Cort could feel its strength. Vitality flowed down his arm and seemed to send sparks inward to his heart. He felt he had the power to do anything, to rescue Dilia, to succeed. His other arm felt weak by comparison, and so he placed his other hand on the staff just above the first. The feeling was utterly exhilarating.

“How do you ever put this staff down?” he said.

“It’s not difficult,” Tirei answered. Cort met the seer’s eyes. They were a soft, light brown, and his expression was filled with something serious, like sorrow or sympathy. “With the staff of the living wood comes great responsibility. Sometimes it’s good to put such responsibility aside.”

As had happened too often since he came to this forest, Cort failed to understand. His face must have betrayed his confusion, for the seer added, “While we hold this staff together, neither you nor I can lie to the other, and we will hold onto it until the staff lets us go. Now listen to me. I am Tirei-sunar of the clan of the hawk, instrument of the whynywir, seer, head of this village, and the father of five. I have lived here my entire life. Now tell me about yourself.”

“My name is Cort.” Cort felt terribly self-conscious. “I am city-born and clanless.” He lifted his chin slightly as he spoke, defying the seer to reject him. “I don’t live in the city anymore. I don’t know where I live. And, Tirei, even without the staff I wouldn’t have lied to you.”

Tirei nodded. “I know that—now. But without the staff, I wouldn’t have been sure. Now tell me about your name.”

“My name? But I already told you,” he said. “It’s Cort. I was named after my father.”

“But ‘Cort’ is not a forest name,” said the older man.

“No, I guess not. Why should it be? I’m not a forest person. His name was something else. Longer.” Cort frowned, trying to get it just right. “Something like Cort-anaran—and so is mine. But no one wants to deal with a long name like that, so no one ever calls me that.”

The older man’s eyes went distant for a moment, as if he were considering something complicated. After a moment of silence, he asked, “Corodh-an-Aran?”

“What?” Cort tried to move his hands to a more comfortable position, but they were as stuck as if they had been glued to the staff.

“Could his name have been Corodh-an-Aran?”

“Yes, I guess that sounds about right. The way you forest people pronounce the old words is a bit different from how we say them in the city.”

“More correct,” said Tirei.

“I guess. Yes, probably; that would make sense.”

“Corodh-an-Aran.” The older man drew out the syllables like a benediction.

“Does it mean anything to you?”

“You don’t know what it means?”

“Should I?”

The seer sighed. “‘Corodh’ is a fine old word but it’s fallen out of common usage. You might say, ‘justice,’ but that’s not exactly right. It has the flavor of being what one is meant to be, doing what one is meant to do, having what one is meant to have. The rightness of things, and also setting things right. A good word. ‘An’ and ‘aran,’ you probably know. Of the forest, or for it. This whole world.”

“Setting things right for Aran? For our world?” The idea pleased Cort. He stood a little straighter.

“Yes, that’s part of it. The forest being and having what she is meant to have. The one who makes sure that happens. Who sets things right for our world.”

Cort smiled. “I like that,” he said. Then, after thinking about it, he added, “Still, it’s only a name.”

“An ancient one,” said the seer. “A good one. And why have you come here, Cort?”

“To become a hunter, like Neder.”

Tirei raised a quizzical eyebrow and glanced at Neder. Standing at Cort’s side, almost out of the range of his sight, the hunter nodded. “But why?” the seer asked.

“To save my friend Dilia, who is like a sister to me,” Cort replied. “More than a sister. My father and mother are dead. My home has been burned down. But Dilia is in the city or on the base somewhere, captive, and I intend to rescue her. It’ll be dangerous. I can’t do it alone. I’ll need a kiri.” He swallowed and added, “Probably no one’s ever hunted in the city before, but I intend to do it, and I’ll succeed, too. And—I didn’t know this at first, but now I do—when I’ve rescued Dilia, I want to bring her back here to the khenaran, and I still want to be a hunter then.”

“This will be decided by the whynywir,” said the seer.

It wasn’t quite a rejection, but it was far from the agreement Cort would have liked. “I understand that, but you’re a seer! You talk with them directly, so you must have some influence with them. Will you help me?”

Again Tirei exchanged glances with Neder. Then he gave Cort a slight, sad smile, suddenly looking weary. “I will do what I feel is right for you, Cort-anaran. For you and for all of Aran.”