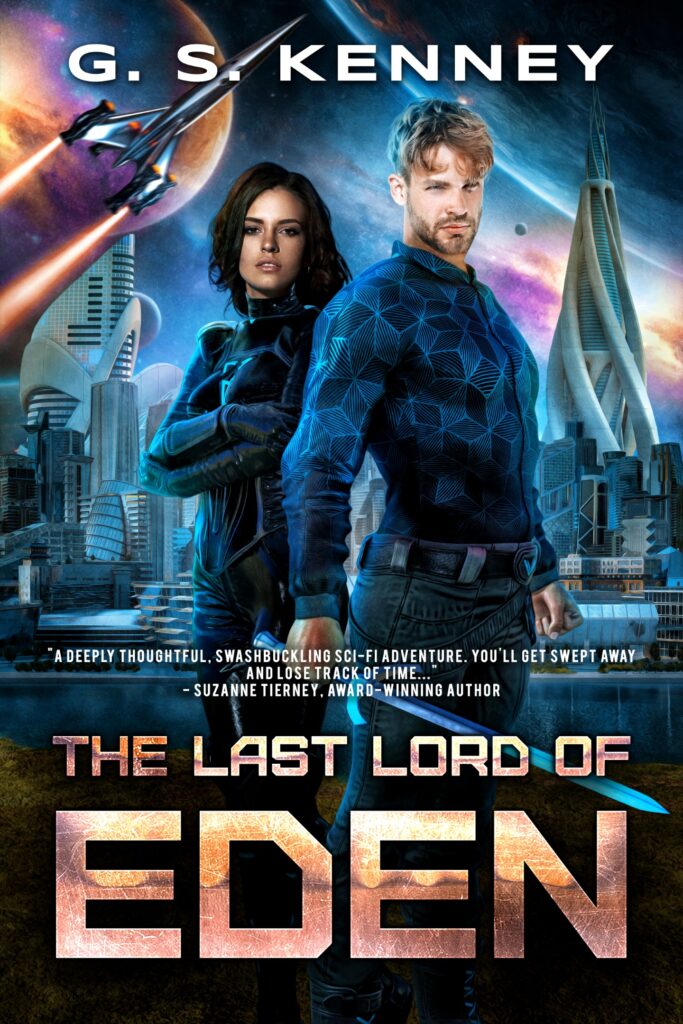

The Last Lord of Eden, due to be re-released with a stunning new cover today, is primarily a science-fiction book with strong romantic elements and lots of adventure. And it also has a metaphysical fantasy element.

Hey, they do call the speculative-fiction genre “science fiction/fantasy,” right? All my books, sci-fi and fantasy alike, occasionally dip a toe into the waters on the other side. Here’s how it works in The Last Lord of Eden.

While visiting his adoptive family on the planet Kestra, our nonviolent, pacifist hero Kell is manipulated into a situation where he must execute someone by beheading. He requests the help of a monastery belonging to a cult that worships Death. Here, he undergoes several weeks of training, where the ultimate goal is temporary possession by Death himself:

Fully awake, Kell felt like he was sleepwalking. He moved as if in a dream, no thought turning in his mind, his bare feet noiseless in the dark corridors of the temple. He passed open rooms, through the entryways spilled in silver moonlight, past the soft sound of sleep-drugged breathing, past bathing rooms, prayer rooms, practice rooms, the kitchen, the refectory.

He paused in a garden cloister. The green of the plants turned to shades of silver and black in the lucid moonlight. No wind stirred. Fever magnified his senses. The air was fresh with the scent of living plants and earth, the more distant smell of compost and of men. Every crack and chink in the stonework of the surrounding buildings scratched against his eyes, the ones in moonlight more sharply, those in the dark as softly as the down in a coverlet. He could have counted each leaf, but he didn’t; he knew their number and the number of their hours. He listened to the worms endlessly turning the soil, a sweet sound that sealed together death and life. He heard plants’ roots growing into the worms’ intimate passageways.

He touched a single perfect rose just opening from its bud, its red color barely discernible in the moonlight. Its petals felt like velvet. They fell beneath his fingertips.

He walked into the Sword chapel.

The Sword blazed through its sheath with an inner light that blackened the rest of the chapel. It shone through the monks who kept watch as if they were insubstantial wraiths.

Whispering to one another, the monks rose to bar his way. The words they chanted melted in the heat of his fever, leaving only harmonies hanging in the air, a minor third, a fourth, an unresolved seventh.

Kell pushed through them. One monk, then another, and then another put a hand out to stop him. They clung to his shoulders, his waist, his legs. Kell stumbled with their weight.

He needed the Sword more than he needed air to breathe.

He reached out.

With the tip of his forefinger, Kell touched the Sword. Fire ran through his body. Lightning possessed him. Thunder roared through the chapel.

The monks who held him dropped back and covered ears and eyes.

Into the silence that followed, the monastery clock tolled midnight.

He burned in a nimbus of fever and blue lightning. He took the sword from the altar and then from its scabbard. He cradled the naked blade against his body like a lover. He turned, his back against the altar, and he waited.

Awakened by the noise, monks ran into the chapel. The old abbot limped into the chapel last. He worked his way through the assembly until he faced the man with the Sword. He observed the cold magnanimity in the blue eyes, the alert posture, the possessiveness with which the man held the weapon. The abbot nodded and said, “Lord Death, welcome.” Slowly, one knee at a time, the abbot knelt at Death’s feet.

The person that was still Kell only in a distant part of his consciousness put a hand on the old man’s head and said, “My son.”

Death acknowledged the silently gathered monks with a nod as he raised the Sword. He slowly drew the sharp edge of the blade diagonally across each of his own cheeks. As the blood flowed, he put the Sword back into its scabbard, then allowed them to approach him. They washed him in rose-scented water, wiping his blood away until the cuts on his cheeks started to scab over. They gently rubbed orange oil on his body, lavender oil into his hair. They belted the sheathed Sword to his back.

The abbot sent word to the king that Death walked again among them. The execution was scheduled for the coming day.

Death kept the Sword at his back in its enameled scabbard. The monks knelt when he passed them in a corridor. The smell of them was delicious, mingling growth and life and decay. And desire. From time to time he touched a kneeling monk gently on shoulder or face or head or arm. The visible marks left by his touch did not disappear.

Death did not sleep. All night, he stalked the corridors of the monastery like a tiger pacing in its cage. In the morning, an elderly monk was found dead in his bed with his hands folded on his chest, his eyes open, and a smile on his mouth. Tiny red, purple, and blue marks near his mouth looked like a flight of butterflies escaping.

One cane of a rosebush, its flowers barely out of bud, stood withered and dried in the garden as if it had been dead for years.

As the clock tolled six, Death watched the sun rise from his monastery’s clock tower, turning first the hills, then the palace towers, then the city from purple to orange to gold. A cool breeze carried the scent of wood ovens and fresh breads and pastries. It magnified the sounds of animals and people stirring.

Death smiled with a fierce joy. Everything he saw and heard and smelled and touched was his.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this excerpt as much as I enjoyed writing it. You might say that Death is a real character in this book, and not an unlikeable one — given that he is, well… Death.

(c) Copyright 2019 by G. S. Kenney. All rights reserved.